Project Background

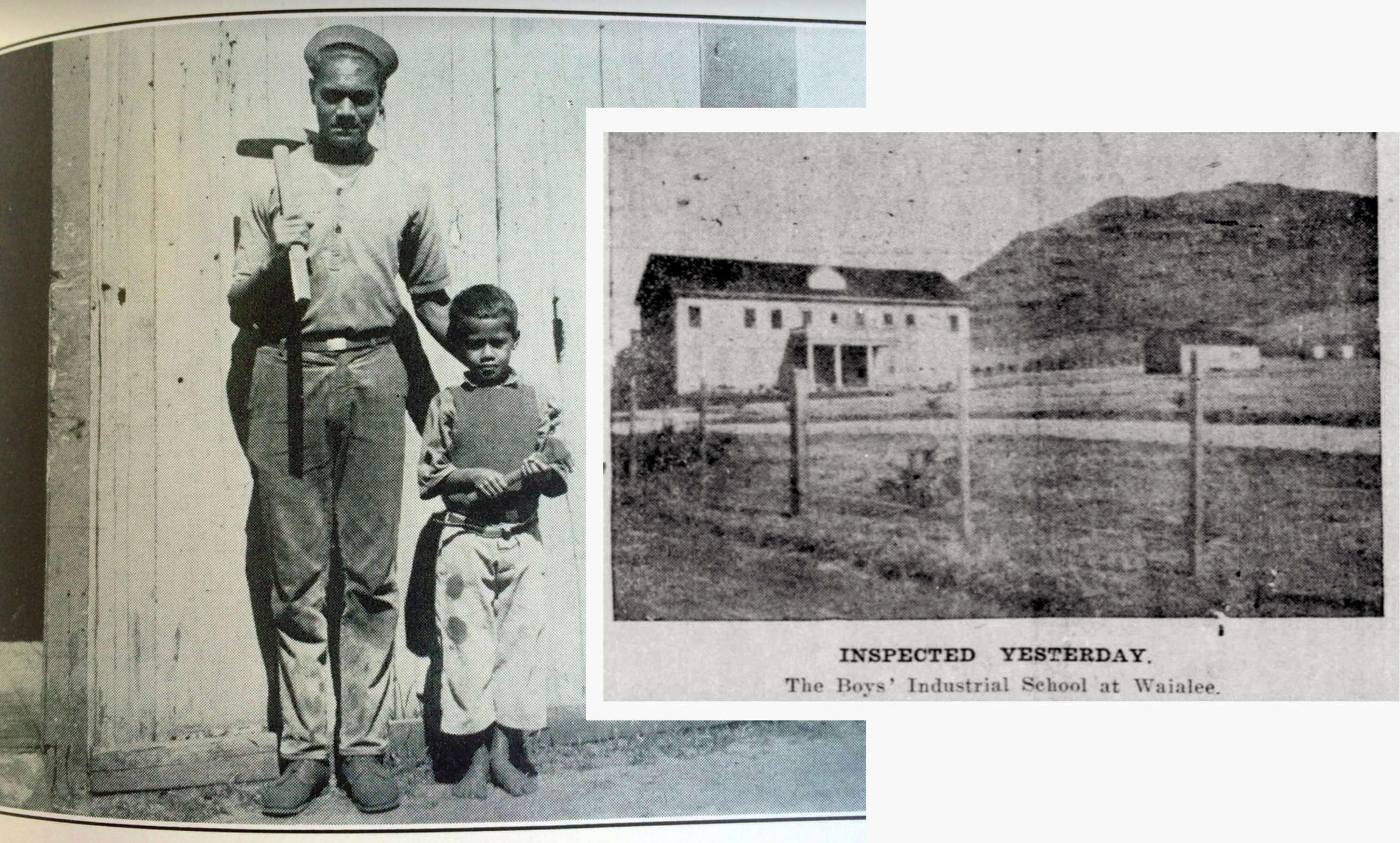

In May 2022, the US Department of Interior issued a Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report. The report is the first systematic accounting of the history of schools by the US government that "systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies to attempt to assimilate American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children through education." The report included 7 institutions located in Hawaiʻi. This research project focuses on several of those institutions, which effectively incarcerated a disproportionate majority of Native Hawaiian children who were convicted of petty crimes or vague condemnations like "waywardness." These institutions include the Waialeʻe Training School for Boys, the Kawailoa Training School for Girls, and the Waimano Home for the Feeble-minded (as it was called at that time).

The project title invokes an ʻōlelo noʻeau (proverb) about the precious nature of child-parent bonds, "He lei poina ʻole ke keiki," meaning a child is like a lei never forgotten. This saying recalls the way children cling to their parents, adorning them like a lei (flower garland). The children kept at these "schools" were ripped from such close relationships when they were institutionalized for years at a time. This research began before the federal report was issued but has new urgency as the government has stated a desire to further investigate this history and pursue some sort of reparative justice. The overall goal of the project is to provide further public engagement with this history, which is not well-known in the Hawaiian context. The work involves archival research, oral history interviews, building a website with digitized resources like story maps, and community engagement.

Student Role

The overall goal of the project is to provide further public engagement with this history of government institutions that forcibly took in children in Hawaiʻi. Accordingly, the work involves archival research, oral history interviews, building a website with digitized resources like story maps, and community engagement. The SPUR student will work closely with Dr. Arvin to identify the areas of this work that they are particularly interested in or suited to, and Dr. Arvin will shape the specific tasks for the student accordingly. However, in general, the student will conduct research on (1) the histories of the sites where these institutions were, looking for traditional land use, moʻolelo (traditional stories/legends related to the area), and the meaning of the place names around the schools; (2) digitized newspaper accounts related to the histories of these institutions - in English and/or in Hawaiian language if the student has Hawaiian language expertise; (3) establishing similarities and differences between these institutions in Hawaiʻi and the boarding schools in the Native American contexts and (4) developing a website to share the results of this research and provide some interpretation of the sources they find for a general, public audience.

This work is important and timely given the 2022 report. The student will gain hands-on skills with conducting original research, analyzing primary and secondary documents, forming their own arguments based on historical evidence, and writing about this history for the public. The student will also be immersed in Hawaiian history and Indigenous Studies scholarship, and be able to connect with our growing U of U community of faculty and students in Pacific Islands Studies.

Student Learning Outcomes and Benefits

The learning outcomes for the student researcher are tied to the following questions about the practice and meaning of history in Indigenous contexts:

*What is history made of?* The student will consider a variety of primary and secondary sources, including genealogies, moʻolelo (stories, legends), newspapers, journals, oral histories, songs and more. The student will learn how to identify, analyze and compare primary and secondary sources, and use these sources to craft original historical arguments.

*Why and how does history matter?* While the history of these institutions may seem distant to some, as the first reformatory opened in 1865 and the training schools operated through the 1950s, as the federal report underscores, this history still has impacts on lives today. The student will learn how people today remember, connect to, and revitalize historical events and narratives.

*How can history impact the future?* The student will reflect on what lessons past and contemporary social movements in Hawaiʻi offer everyone about why knowing our histories matter, and how knowing our histories can help us shape change for the future. The student will be able to develop their own writing and other creative responses to this history through the website we will work on building together.

More specifically, the student will gain expertise in Hawaiian history as well as Native American history. These fields are shaped in important ways by interdisciplinary engagements with Indigenous Studies, Ethnic Studies, and Gender Studies. The student will be expected to engage in a scholarly manner with categories of race, gender, sexuality, and disability, all important concepts in Humanities and other scholarly fields.

Maile Arvin

At the core of my approach to mentoring is establishing mutual expectations, shared values, and regular communication early in our relationship, and to periodically directly check in and adjust our plan as needed. Mutual expectations means we talk in detail about how we will work together, developed through sharing what our working styles are. Shared values means we explicitly address how we will handle any difficulties that may arise - for example, in the past, I have explicitly agreed with students that we will prioritize taking care of our mental and physical health over work, so that, for example, we reschedule meetings when someone is sick without any question. Whatever agreements we make, I set up systems for regular communication and meetings, so there are frequent opportunities to check in and assess the student's progress towards various project goals. This likely means meeting in person or online at least twice a week.

Each student I work with is different, and therefore every relationship is different. However, I work hard to build trust and accountability between us, providing more direct support and training (such as in navigating the databases and software required in the research) at the beginning of our relationship and then providing support as needed once the student feels confident in managing the research tasks they have been assigned. I will give at least weekly feedback on the student's progress with research tasks. In giving feedback, I strive to be both honest and encouraging - providing critique when needed, but also offering tools to correct what needs improvement.

Other mentoring activities include helping the student develop their own research poster and discussing future career paths.